Tuesday, December 2, 2008

Experience Points and Leveling Up

Level Experience Points:

level 1 = 1,000 exp.

level 2 = 3,000 exp.

level 3 = 6,000 exp.

level 4 = 10,000 exp.

level 5 = 15,000 exp.

level 6 = 21,000 exp.

level 7 = 28,000 exp.

level 8 = 36,000 exp.

level 9 = 45,000 exp.

level 10 = 55,000 exp.

Monday, October 6, 2008

Click-Through

What is Click-Through?

If you’re new to RocketOn, Click-Through is the ability to click on links, expandable menus, text entry fields, and other interactive elements of pages while you have RocketOn fully open and your avatar walking about. Normally, while you have RocketOn open, you’ll be able to walk anywhere you click. With Click-Through, you can click on links as well! You can also click on buttons and text fields.

If you’re new to RocketOn, Click-Through is the ability to click on links, expandable menus, text entry fields, and other interactive elements of pages while you have RocketOn fully open and your avatar walking about. Normally, while you have RocketOn open, you’ll be able to walk anywhere you click. With Click-Through, you can click on links as well! You can also click on buttons and text fields. Getting Click-Through to Work:

How do I get Click-Through?

-Silent Ellipsis & Max

Friday, September 19, 2008

Talk Like a Pirate Day!

Ahoy mateys! This be "talk like a pirate day," where ev'ry last one of ye be encouraged to talk like a brethren of the coast!

If yer friends don't keep in t' spirit o' t' holiday, ye can prank 'em wit' our Pirate Boat an' Pirate Flag pranks, an' ev'ry word out o' der mouths will become more appealin' to t' ears o' a brethren of the coast!

So be sure to stop by yer nearest RocketOn Store an' gather ye up a bounty of pranks. A grog-filled talk like a brethren o' t' coast day to ye!

-Silent "Landlubber Stabbin" Ellipsis

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

Personal Rooms

What is a personal room?

Whenever you're using RocketOn, you're in a room. The room you're in determines which other users, and sometimes what kinds of RocketOn objects you'll see, so even if you and your friend are both on www.google.com, you might not see them because they're in a different room (if so, a signpost will pop up that you can click on to go to the next room on the same site).

Personal rooms are rooms created and owned by users. You can control who can enter the room and customize it with photos, blurbs, and more! Personal rooms are places you can express yourself, or places to meet up with and hang out with your friends without being overwhelmed by the number of users in public rooms.

How do I go to someone's personal room?

To visit someone's personal room, you can either go to their profile or search for them using the new Find People tool. You'll see a button that says my rooms on their profile, or view rooms in the search box. Click on this to bring up a list of their rooms, then just pick one and go. When you're in someone else's personal room, you'll see a box in the corner of the screen with buttons to leave the room, report the user (if their room contains offensive material), or to check out their profile (a fast way to get back to their personal room list).

While you're in someone else's personal room, you can see and interact with all of the room objects they've added. You can play the youtube videos they've added, listen to the radio station on their radio, or click through their flickr photos if they've added that setting.

While you're in someone else's personal room, you can see and interact with all of the room objects they've added. You can play the youtube videos they've added, listen to the radio station on their radio, or click through their flickr photos if they've added that setting.Hold your mouse over the object and clickable buttons, like the arrows here, may show up.

How do I create a personal room?

Creating a personal room is easy. Go to your profile and you'll see a my rooms button. Click on it and it will bring up a list of your personal rooms. Now you'll see a create button - click on it to bring up the room creation menu. Here you can name your room and set who can join the room. Once you're ready, click create and you'll be taken to your new personal room.

Once you've created the room, you'll see a box in the corner that shows you a variety of objects you can add to your room to make it your own. Click on one of the objects to add it to your room.

Once you've created the room, you'll see a box in the corner that shows you a variety of objects you can add to your room to make it your own. Click on one of the objects to add it to your room.All of the objects have similar controls. You can drag the object around the screen and put it wherever you want. If you click the options button, you'll be able to customize the object (for example, you need to go to options to add a url for any youtube video you want to have on your page).

When you're happy with your object, click save and the object will be placed with its current settings. You can later move or modify any object in your room by clicking on the gear button in the corner (such as in the cow picture above). You'll be able to move the object around or click options again, and can save the object with its new settings. If you change your mind while editing the object, and want it to go back to the way it was, then don't click save - instead click the gear button again, and the object will go back to the way it was before you started editing it.

Now you know everything you need to start exploring personal rooms. Go try it out for yourself and make a room that you can show off to all your friends!

-Silent Ellipsis

Tuesday, September 2, 2008

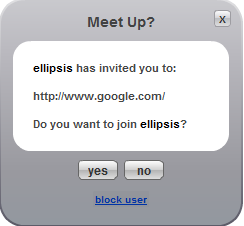

Meet and Join

In Part 3 of our mini-series on overlooked features, we discuss the meet and join me buttons, which can be found in the "Friends" window. You can use these buttons to meet one of your friends wherever they are online, or to ask them to join you on the web page you're on.

In Part 3 of our mini-series on overlooked features, we discuss the meet and join me buttons, which can be found in the "Friends" window. You can use these buttons to meet one of your friends wherever they are online, or to ask them to join you on the web page you're on.How it works: Click on "Friends" in the RocketOn toolbar to view you list of online friends. Choose a friend's name from the list and click on the meet button. Your friend will receive a message asking permission for you to meet them on the website they are browsing. If they approve, you will be sent an invitation to join them. Hit ok and you'll be transported to the page they're browsing. It's a simple and fast way to find your friends.

Note: If your friend has selected "friends can meet me without my permission," then when you click meet, you will immediately receive an invitation to join them (it won't ask your friend permission first).

Step by Step Example:

Step 1: Click on the "Friends" icon (the smiley face).

Step 2: Choose the name of a friend who is online from the list and click meet.

Step 3: Upon their approval, you will be asked to join them.

Step 4: If you approve of the website they are on, click yes.

Result: You will be transported to the website your friend is currently browsing.

What if you want your friend to come to the site your on, instead of the other way around? That's when you use the join me button.

How it works: Click on "Friends" in the RocketOn toolbar to view your list of online friends. Choose a friend's name from the list and click join me. Your friend will receive an invitation to join you on whatever page you're browsing. If they approve, they will be instantly transported to your side.

Note: Even if you can already see your friend on the same website, they might be on a different page of that site. For example, you might both be on youtube, but looking at different videos. If you ask your friend to join you, they will move to the same page, so you can use this feature to make sure you and your friend are seeing the same content.

Step by Step Example:

Step 1: Click on "Friends" icon (the smiley face).

Step 2: Choose the name of a friend who is online and click join me.

Result: Your friend will be sent an invitation to join you. If they accept, they'll be transported to the same page you're browsing.

The "Overlooked Features" series is brought to you by Food Lover and Silent Ellipsis.

P.S. Starting next week, we'll begin a series on brand new features that have just been added! Keep an eye out for the new features, and come here for tips on how to get the most out of them.

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Notes

Continuing our Overlooked Features series, this week we discuss the ever-lovable note! You can send a personalized note directly to a friend, or surprise them by leaving a note on their favorite website.

How it works: Once you buy a note, it will appear in My Stuff. To leave a note for your friend, go to the website you wish to place it on. Find your note in My Stuff and click the “give” button. You will then be prompted to choose a friend from the drop down list and enter your personalized message. Once you are done, click the “place on URL” button and your note will pop-up on your friend’s screen when they visit the site. If you wish to send the note directly to your friend, click on the “send it” button instead of the “place on URL” button.

Step by Step Example:

Step 1: Buy a note from the store.

Step 2: (if you wish to leave the note on a website): Go to the website where you want to leave the note for a friend (ex. www.vh1.com ).

Step 3: Find the note in My Stuff and click the “give” button.

Step 4: Choose a friend from the drop down menu and type a personalized message.

Step 5: Click the “place on URL” button to leave the note on the website, or click the “send it” button to place the note directly into your friend’s My Stuff.

Result: When your friend visits www.vh1.com or looks in My Stuff, they will be happily surprised to discover your note!

The "Overlooked Features" series is brought to you by Food Lover and Silent Ellipsis.

Monday, August 18, 2008

Doors

Are you looking for more features that will allow you to interact with your friends? Well, you may have overlooked some of RocketOn’s most powerful interactive features. Starting this week, we're going to be posting explanations of some of the overlooked features that can totally change your RocketOn experience. Up this week: DOORS- A door allows you to share your favorite sites with friends by opening up a portal from one webpage to another.

Are you looking for more features that will allow you to interact with your friends? Well, you may have overlooked some of RocketOn’s most powerful interactive features. Starting this week, we're going to be posting explanations of some of the overlooked features that can totally change your RocketOn experience. Up this week: DOORS- A door allows you to share your favorite sites with friends by opening up a portal from one webpage to another.How it works: Once you buy a door, it will appear in My Stuff. To create a portal using your door, simply drag and drop it onto any webpage. It will then prompt you to enter the URL of the site you wish to share with your friends. Other people on the original webpage will see your door. If they click on it and approve, they will go to the URL you entered.

Step by Step Example:

Step 1: Buy a door from the store.

Step 2: Open My Stuff and drag the door onto a webpage (Ex. http://www.google.com/).

Step 3: Enter the URL of the site you want people to visit (Ex. www.mtv.com).

Result: Everyone on www.google.com will see your door and can click on it. Once they click and approve, they will be taken to www.mtv.com!

Each person on the page will be able to use the door, but they can only use it once. Fortunately, doors aren't expensive at all, so you can make liberal use of them.

The "Overlooked Features" series is brought to you by Food Lover and Silent Ellipsis.

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Virtual Worlds and Moral Choices

There are a variety of ways we might answer this question, the first of which is presented by “The Horde is Evil.” We might think that there is moral significance to a choice of character type in an MMO. By choosing to be represented in the world by a character associated with evil, you are presenting an implicit approval of that evil. This doesn’t seem right to me. Choosing a character type in an MMO, especially if by that we mean a character’s race, is a matter of choosing a setting. You’re not choosing any actions your character has performed, but choosing the cultural and historical background of that character. If that counts as a morally weighted (and negative) choice then you could just as easily say that choosing to play World of Warcraft is a morally negative choice to begin with, because you’re choosing to play a game in a world that includes not only evil, but rampant warfare. You could instead have chosen to play a game, or even an MMO, that includes no war, no combat, and no evil. Insisting that a choice of setting in a virtual world is morally weighted is tantamount to declaring that MMORPGs are, on the whole, morally evil, which beyond being simplistic isn’t an argument that’s going to have any traction among gamers.

So if I disagree with the thesis of “The Horde is Evil” does that mean I don’t believe that decisions in a virtual world can have moral weight? No it does not, but we might mean something else entirely by that. Many people will agree that a decision that affects the happiness of others carries implicit (or explicit) moral weight, and online virtual worlds allow users to affect each others’ game experience. If I stick around a spot where a rare treasure appears on a timed basis and continually gather it, I might be preventing other players from gathering it; if I use a macro to collect massive quantities of a valuable resource, I devalue that resource that other plays have earned legitimately. Beyond these unintentionally side-effects of my actions, there is the phenomenon of “grieving.” Grievers are bored or insecure players (or both) who intentionally go out of their way to ruin the game experience for other players. This could entail verbal harassment, repeatedly killing another user’s character, joining a party and then refusing to help when they run into trouble, or a variety of other activities intended to provide amusement by frustrating others. As grieving is an activity that directly affects other real, living people it’s clearly a moral decision, but is it a very weighty one? In the majority of cases the worst consequence of grieving is temporary annoyance and frustration. What’s more, this behavior isn’t really specific to virtual worlds. Even if it takes a particular form within a virtual world, the behavior is essentially harassment, and the virtual world in this case is simply a medium through which the harassment occurs. The virtual world is playing the same role that a phone does in a prank phone call: the content of a prank phone call does tell us much about the moral nature of telephones.

There might be a third thing that we mean by saying that a decision in a virtual world can be a moral decision – we might think it’s moral or immoral not because of the impact it has on players, but because of the way it affects the virtual world itself. This strikes me as the interesting concept, because it’s not immediately clear what to make of it. On the one hand a virtual world is fictional, so it seems that the events that occur within it shouldn’t be any more weighty than they are in a book or film. However, the nature of a virtual world is that it is participatory: many people are invested in the virtual world (emotionally and financially), and they can shape it through their actions.

We may need a few more conceptual tools before we evaluate this idea. First, I will suggest that what is fundamentally capable of being moral or immoral is choice. When we say that a person is moral, we mean that they are a person who makes good moral choices. Part of the reason I reject the thesis of “The Horde is Evil” is because of this. I don’t think it’s coherent to suggest that a race (such as orcs) can be inherently evil – they can only be evil by virtue of their choices. The second idea that I am going to put forward as useful for our purposes here is that morality, at some root level, depends upon value. What I mean is that whether you are a deontologist, a consequentialist, or virtue theorist, you should think that what it means for a decision to be moral is that it promotes something of value. The exact nature of this question can be debated, but I don’t think it makes sense to talk about a decision having moral import without suggesting that something of value is affected by it.

Now let’s see how these concepts fit in with our thoughts about virtual worlds. If we’re going to judge something as moral, we’re judging a choice to be, so the actions taken by the computer can never be considered moral or immoral (though the decisions of the designers and programmers that resulted in the computer performing that action might). Rather, we’re concerned about player choices, as manifested in the actions of their avatars. What’s more, we’re concerned with how these choices affect things of value within the virtual world. Given that the world is, as its name implies, virtual, and exists primarily in the minds of the players (as mediated by the game), it seems to me that the only kind of value to be found within it is instilled in it by humans. This kind of value is easy enough to find, however: virtual worlds are largely about identifying with the interests of your character or avatar, and acquiring possessions, experience, and the like for them. A player might also identify with the interests of their guild, faction, or with the virtual world as a whole.

So what kind of effect can a player have on things of value? In truth, in most persistent worlds the answer is “very little.” In every persistent world I’ve ever seen, player characters never permanently die, NPCs cannot be killed, and monsters and NPC allies will eternally respawn. In most worlds it’s also not possible to take territory or possessions from other players, and all factions in the game will exist for as long as the world persists. These static virtual worlds actually disarm most of the moral weight of decisions within them, but if a world were designed to include more significant consequences of actions, then the idea of morally weight decisions by virtue of their influence on the world would become very real very quickly.

Let’s look at a concrete example. In the posts I referred to above, one topic of discussion is the fate of monsters called murlocs at the hands of adventurers who slaughter them in huge numbers in order to complete quests. There is something disturbing about how this is presented to the player – you are committing acts of genocide – but within persistent world, there are no lasting effects of a player completing the quest. The moral impact of killing murlocs is only the impact it has on the game experience of the player(s) killing them. Let’s consider an alternative possibility: the number of murlocs in the world is limited. Perhaps the murlocs reproduce at a certain rate, and if the rate at which players kill them exceed the rate at which they reproduce, their population will dwindle. Now we have the possibility not only that a player can have the visual experience of killing a murloc, but that their choice can have an effect on the world. If murlocs are slaughtered in large enough numbers, they might become extinct on that game server. What about a world in which player characters can die permanently? In these situations it seems like the possibility exists for in-game decisions to have a real impact on things of value to other players.

More generally, what I’m suggesting is that if players can shape the virtual world that they are in, they have the potential to promote things they value within that virtual world, whether that be immersive gameplay (in which case playing an villain could actually be a morally positive decision, by allowing for a more dynamic game world), the aesthetic features of the world, or murlocs. In this situation a destructive player can make a morally significant decision within the context of the virtual world, as can a constructive player. Given the nature of most worlds today, this is more an issue of the potential of virtual worlds, but it is still of immediate interest, at least to people like me.

After Raph Koster’s “The Other Side,” “The Evil We Pretend to Do,” Terra Nova’s “The Horde is Evil” and DuoCenti’s “The Murloc’s Family.”

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

2D and 3D Worlds

ROCKETON is a 2D virtual world that can layered onto any website. One may be tempted to question, then, how it intends to compete with the various 3D virtual worlds out there, such as IMVU or Google’s recently announced Lively. I’ll address this in two parts – first, dealing with the assumption that 3D graphics are better than 2D graphics by their nature, and second by talking about how a 2D format is specifically advantageous for what ROCKETON is trying to accomplish.

The advent of 3D game technology has opened up new possibilities for games. It has allowed for an unprecedented amount of graphical detail, allowed for shifts in perspective, and perhaps more importantly added a dimension in which objects can move in virtual space. There are, however, downsides to 3D graphics, including the problem hinted at in the post just below this one: the problem of the uncanny valley.

More generally, though, a key problem for 3D games is the inherent decrease in visual abstraction, which results in 3D graphics aging very quickly.

For example, Final Fantas y VII was lauded for it’s state-of-the-art graphics in 1997, as shown in the picture to the left. This was seen as a prime example of the amazing possibilities of 3D graphics when it was first released, but just a couple of years later looked dated.

y VII was lauded for it’s state-of-the-art graphics in 1997, as shown in the picture to the left. This was seen as a prime example of the amazing possibilities of 3D graphics when it was first released, but just a couple of years later looked dated.

This isn’t the fault of the artists working on the game, but is a natural consequence of the switch to polygon-based graphics. There is an added level of visual abstraction in the use of a 2D image to represent a 3D space, and it is a level of abstraction we’re very familiar and comfortable with – we make the same allowances whenever we draw pictures representing 3D objects in the world.

A 2D game also presents privileged perspectives of the objects in the world, which can make it easier to have a consistently appealing aesthetic presentation. A month after Final Fantasy VII was released, Konami released Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, a throwback to 2D sidescrolling that was able to build upon existing methods of making convincing 2D art and use layered backgrounds to create a game that is an aesthetic achievement even by today’s standards.

This isn’t to suggest that 2D games are inherently superior to 3D games – I’d be very sad not have played many of my favorite 3D games from the last 10 years – but that 2D and 3D games have comparative advantages, and in some cases 2D graphics will serve the vision of a project better than 3D graphics can.

ROCKETON is such a project that can make better use of 2D graphics than it could 3D graphics. The vision for the application is to allow users to bring their avatars to any site. Google’s Lively advertises that it can be put on any site – but what that means is that a point of access to the virtual world can be embedded on any site. There is no relationship between the virtual space and the site it is on. There is a French virtual environment called “Yoowalk” which tries to use websites as the backdrop for a 3D space, but the result strikes me as extremely awkward. The reason is pretty straightforward: websites are only 2-dimensional in nature. Most websites consist of text and pictures, both of which exist in two dimensions. In order to create a relationship between a virtual space and a website, the space has to accommodate the form of the website. What’s more, 3D environments take up more resources and take longer to load than a 2D environment does, which slows down the browsing experience and makes the environment less accessible. Finally, navigation in a 2D environment is more intuitive than it is in a 3D environment. A mouse only moves in two dimensions, and so can perfectly represent a range of possibilities in 2D but not in 3D space. 3D environment have shifting perspective, and objects in front of objects are common, which can make it hard to select the object you intended. A 2D environment offers a more fluid experience, in which a user can pick up and go where they want immediately, without having to wait for a long load time or figure out how to navigate a 3D space. Combine this with the fact that users know that they’re in-game property won’t be visually obsolete in two years time and you have all the components needed for a successful virtual world.

-Ellipsis

Tuesday, July 8, 2008

Friday, June 27, 2008

The App

First, what is ROCKETON? It describes itself as a “Parallel Virtual World,” meaning that the virtual space that application takes place on exists simultaneously in many places (in this case, on various sites). The application itself is an avatar-based app, where you can create, customize, and socialize with a flash-based avatar. The virtual space also includes other activities and objects for you to interact with, including games. That’s an interesting point for this question – one of the buttons on the toolbar is labeled “Games,” which seems to imply that the other aspects of the application aren’t games. I also find that on a regular basis I refer to it as “the app” to avoid any confusion. I’ve also called the game a “social networking tool” before. Of course, sites like MySpace and instant messaging programs also qualify as “social networking tools, and I wouldn’t call those games.

That might make the question seem decisive, but there are a couple of other considerations that complicate it. First of all, the app is a virtual world, with its own resources and rules. A social networking tool that doesn’t count as a game might offer purchasable tools or features that make it a more effective tool, but they don’t have resource systems used to acquire virtual possessions for possession’s sake. The existence of virtual resources creates a boundary between the avatar and the person it represents – when I use a chat program, I’m using a tool to communicate information about myself. I can do this with ROCKETON, but I can also meaningfully talk about my avatar independently from myself. I don’t have a pet turtle, but my avatar might. I don’t know how to play the guitar, but my avatar can really wail on his virtual guitar. The fact that items exist in the virtual space for their own sake makes the virtual space game-like.

But there’s an even more important reason why the application makes social interaction game-like. If we look specifically at the chat feature of the game, we might be tempted at first to think of it as functioning exactly like an IM program such as AIM or MSN. However, when I type a sentence for my character to speak in ROCKETON, everyone in the same virtual room can hear me, and everyone in a different virtual room cannot. This means that my avatar has a location within the virtual world. This limitation actually creates a new concept that structures the way I interact with websites, and there’s nothing more game-like than utilizing limitations to create new kinds of experiences.

In short, though it’s accurate to call the application a social networking tool, I also think it clearly counts as a game, and I would even go so far as to say that it provides a uniquely game-like social experience by providing a structured way to socialize with other users through your avatar without being your avatar. The status of the application as a game might be more clear in the future as we release more features that allow users to participate in large-scale goal-oriented activities with their avatars.

Ellipsis

Virtual Worlds & Online Diaries

Would you have your avatar act it out in real-time? Or would you create a space, like a virtual home, in which you share and express your life? Maybe the objects in the virtual home would mirror your real home. Maybe your family and friends would be represented by avatars or appear in a virtual scrapbook.

Realistically, most people don't have the time to create a meaningful virtual reenactment. However, if there were an easy scripting tool, along the lines of a blogging mechanism, then creating a virtual diary using a set cast of avatars that you dress up might not be so daunting.

Another possibility is to focus less on your real life and instead create a diary that’s about your cyber life. I could envision people creating a diary of the places they visited online and what they thought. Using ROCKETON's browser plug-in, this could be easily automated. It could record the URLs a person visits, and that person could then add a running commentary using text, audio, video or photos. This would be a dairy of your thoughts while surfing, and like all diaries, it would be selective, only focusing on the highlights of each day in cyberspace.

I'll keep ruminating on this. In the meantime, I'd love to hear other people's thoughts on how a diary might take shape in a virtual space like Second Life or ROCKETON.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Games and Game-likeness: Defining the Gaming Medium

In reality, there is no universally agreed upon definition of a “game.” We can describe them in general terms, however. Games are interactive; games offer player choices; games either have built-in goals or a means for players to develop goals as they play. There are a variety of features that are common in games, or important in certain genres, but I think these are the most fundamental features that make an experience a gaming experience.

Here’s a different approach. Marc LeBlanc has compiled a list of 8 aspects of games that make them fun (http://www.8kindsoffun.com/): Sensation, Fantasy, Fellowship, Discovery, Narrative, Expression, Challenge, and Submission. If we consider, however, not just what makes games fun, but what makes them uniquely fun, we see that other media can fulfill some of these kinds of fun just as well, if not better, than games. Movies offer plenty of sensation, novels contain compelling narratives, and any kind of social networking site can offer fellowship.

So the real question is how can games offer these kinds of experiences in a unique way? By approaching them in a game-like manner. For example, if a story isn’t linear, or preset, but branches or can be traversed in a non-linear way, then it is not just presenting a narrative, but a game narrative. This makes the narrative more than just a story – it’s a way of exploring the possibilities of gaming. A compelling game narrative doesn’t just present the player with a story – it lets the player see the story being created as the game progresses. Similarly, every kind of fun on the list above can be approached in a game-like way.

Why should we care if a certain experience is game-like or not? Some of us like to call ourselves gamers, or say that we love gaming, but if we don’t know what goes into a gaming experience, what do we mean when we say that? Games may very well be the medium of the 21st century in the same way that film was the medium of the 20th century, but if so, then games need to have a clear sense of what it is they have to offer. If we ever want to see the full potential of games, we need to find and explore the parts of an experience that make it into a good gaming experience.

Ellipsis

Friday, June 13, 2008

Welcome to the ROCKETON Blog!

We're in Closed Alpha right now. If you've been invited to join, we welcome your feedback and ideas. If you haven't been invited, click here to sign up!

Starting a blog on Friday the 13th isn't exactly good luck, but we'll see if we can survive the day. That said, there's been no catastrophes so far.

A lot of people are asking when we're going to open up to the public. All we can say is that ROCKETON is evolving quickly. You'll see that we're adding new features all the time. We'll open ROCKETON up to the public and launch when we feel it's ready.

Stay tuned, and we hope you enjoy the experience!

Captain Hoff